China Brands, Marketing & Consumers

The Legendary Lao Gan Ma: How Chili Sauce Billionaire Tao Huabi Became a ‘Chinese Dream’ Role Model

The story of Lao Gan Ma founder Tao Huabi.

Published

3 years agoon

PREMIUM CONTENT

You might know the chili sauce Lao Gan Ma, a household name in China. But perhaps you’re less familiar with the story behind the sauce and its founder, which has inspired millions of people and has made ‘Old Godmother’ Tao Huabi a notable figure in Chinese contemporary culture today. For many, the successful businesswoman and ‘chili sauce queen’ is an embodiment of the ‘Chinese dream.’

This is the “WE…WEI…WHAT?” column by Manya Koetse, original publication in German by Goethe Institut China (forthcoming), visit Yi Magazin: WE…WEI…WHAT? Manya Koetse erklärt das chinesische Internet.

Lao Gan Ma t-shirts, Lao Gan Ma phone covers, Lao Gan Ma bracelets, and even Lao Gan Ma airpod cases – Lao Gan Ma is more fashionable than ever in China today.

The celebrated brand is one of the country’s most well-known chili sauce labels, and it pops up in Chinese media and online culture every single day; not just because of its tasty condiments and other food products, but also because of the company’s remarkable history and evolution.

Besides the popularity of Lao Gan Ma’s crispy chili oil, it is the story of founder Tao Huabi (陶华碧) that plays a crucial role in the brand’s contemporary success. It is her face you see on the recognizable packaging design that has become a household product and is now also famous in many countries outside of China.

The iconic Lao Gan Ma, image via www.szmtzc.com

The brand name ‘Lao Gan Ma’ (老干妈) literally means ‘Old Godmother’ and refers to Tao Huabi herself. She is the creator of the famous chili sauces who has, over time, become the embodiment of the ‘Chinese dream.’ By following her own path and relying on her business instinct, Tao rose from poverty and became one of China’s richest women.

In order to explain why Tao Huabi is such an iconic figure in China today, let’s look at this famous female entrepreneur by highlighting the different stages of her Lao Gan Ma journey.

1: The Young Tao Huabi: “If I Hadn’t Been Strong, I Would’ve Starved”

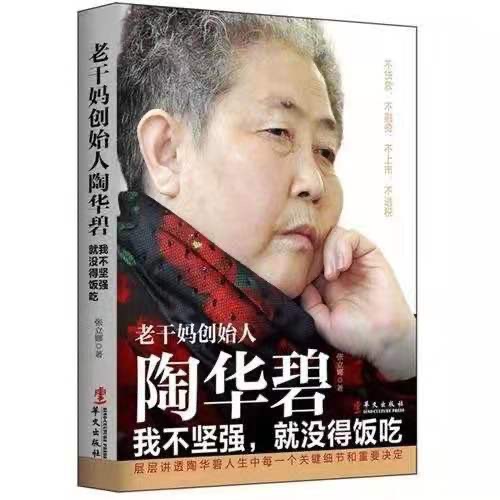

“There are many successful businesses entrepreneurs who have experienced hardships, but there are few whose starting point was as low as Tao’s.” These are the opening lines of a popular book about Tao Huabi, written by Zhang Lina (张丽娜), telling the story of her life.1

Tao Huabi was born in 1947 in a small village in Meitan County, Guizhou, one of China’s poorest provinces. She was the eighth daughter in her family (her parents had actually hoped to finally have a son), and her parents struggled to feed and clothe their children, let alone give them proper education. Tao was not taught how to read and write.

The biography about Tao Huabi describes how Tao spent her younger years chopping wood, cooking and farming. The title of the book is If I Hadn’t Been Strong, I Would’ve Starved (我不坚强,就没得饭吃), and it is telling of how Tao’s younger years were all about being hungry and finding ways to keep on going.

Tao Huabi’s biography, written by Zhang Nali. Image via Shanghuibs.

During the Great Chinese Famine (1959-1961), Tao dug for wild vegetables and tried various ways to eat plant roots, using whatever she had to try and make the little food they had taste better. This is how poverty and hunger drove the young Tao to make her very first chili sauce. The natural sauce, made from medicinal plants from the mountains and home-grown chili peppers, was loved by the entire family.

When Tao was 20 years old, she married her husband, who worked as an accountant with the local geological team. They had two sons together. But the happy life of the young family did not last long as just a few years into their marriage, Tao’s husband became seriously ill with liver disease.

Tao now found herself in an incredibly difficult situation; she was uneducated, illiterate, and had no official working experience. But she needed to provide income for her family as they had no money to cover her husband’s medical costs and pay for the food and education of their two sons. The 30-yuan monthly income of her husband was nowhere near enough to help the family.

The situation led Tao to head out of the countryside for the first time in her life to go to the city of Guangzhou to find a factory job as a migrant worker. She brought her own homemade chili sauce with her to the faraway city and used it to flavor her steamed buns when she couldn’t afford any other food. She also shared it with her co-workers, who found her chili sauce to be delicious.

Unfortunately, Tao’s efforts could not save her husband’s life. She soon became widowed and, heartbroken, had to return back to Guizhou to take care of her two young boys. Now that she had become the sole caregiver and provider of her family, she started selling rice curd and also set up a street stall selling vegetables at all hours of the day, often working until 4 in the morning.

Her passion for cooking kept following Tao wherever she went. One day, when Tao’s sons were already grown up, she visited a noodle shop after work and complained to the female shop owner that their cold noodles were not authentic enough. After Tao gave the lady her tips and tricks on how to improve the noodles using chili oil, she was offered a job at the noodle stall. The experience at the shop eventually gave Tao the idea to start her own business.

2: Inspirational Business Journey: “Selling the Flavor”

In 1989, when Tao was 42, she set up her own little “Economical Restaurant” (“实惠饭店”) in the Nanming District of Guiyang, Guizhou. Although she just served simple noodles, she mixed them with her own spicy hot sauce with soybeans. Tao was beloved in the neighborhood, where she became a ‘godmother’ to poor students whom she would always give discounts and some extra food.

With many local students and patrons visiting her little diner, the noodle shop business soon flourished, but not because of her noodles – it was the chili sauce that kept people coming back for more.

Tao Huabi came to understand the popularity of her condiments when customers came in to purchase the sauce by itself, without the noodles. One day, when her sauce had sold out, she found that customers would not even eat her noodles without the chili. When Tao learned that other noodle shops in the neighborhood were all doing good business by using her home-made sauce in their noodles, she finally realized the true potential of her product.

By the early 1990s, more truck drivers passed by Tao’s shop due to the construction of a new highway in the area. Tao took this as a chance to promote her condiments outside the realm of her own neighborhood and started giving out her sauces for free for the truckers to take home. This form of word-of-mouth marketing soon paid off when people from outside the city district came to visit Tao’s shop to buy her chili sauces and other condiments.

By late 1994, Tao had stopped selling noodles and had turned her little restaurant into a specialty store called ‘Tao’s Guiyang Nanming Food Shop’ (“贵阳南明陶氏风味食品店”), with the chili oil sauce being the number one product.

Two years later, at the age of 49, Tao took the plunge to rent a house in Guiyang, recruited forty workers, and set up her own sauce factory called ‘Old Godmother’: ‘Lao Gan Ma‘ (老干妈). Since the factory initially had no machines, the chili chopping was all done manually. Tao herself, wearing her apron, would also cut chilis at the factory tables together with her workers.

In 1997, the company was officially listed and open for business. Although Tao never had any formal education, she turned out to have a natural talent for managing her flourishing company. Tao’s two sons later also joined the Lao Gan Ma company.

Although the Lao Gan Ma brand became successful almost immediately after its launch, Tao Huabi still struggled for years as a handful of competitors launched fake Lao Gan Ma sauces with similar packaging, and nearly ruined her business. In 2001, when Tao Huabi was 54, the high court in Beijing finally ruled that other similar products could not use the “Lao Gan Ma” name nor imitate her packages. She received 400,000 RMB in compensation ($60,000).

Tao Huabi in her factory, image via Sohu.com.

Lao Gan Ma eventually employed over 2000 factory workers and became the largest producer and seller of chili products in China, reaching a point where the company produced 1.3 million bottles of chili sauce every day. Besides the iconic Fried Chili in Oil and Chili Crisp Sauce, Lao Gan Ma also produces Black Beans Chili Sauce, Tomato Chili Sauce, hot pot soup base, and other condiments.

By now, Tao’s ‘chili empire’ has gone international, as her condiments are sold from the USA to Africa. Tao Huabi once famously said that she does not know all the countries outside of China where Lao Gan Ma is sold, but that she does know that Lao Gan Ma is sold wherever there are Chinese people.

In 2019, Lao Gan Ma was selected as one of the top 100 brands in China, together with other famous national brands such as China Mobile, Huawei, Tik Tok, Tsingtao, and Alibaba.

Lao Gan Ma packaging, image via Taobao.

What is striking about the Lao Gan Ma business model is that it does not follow the usual marketing strategy tactics. The company rarely advertises, there are no celebrity endorsements, no social media accounts or campaigns, the website hasn’t been updated for years, and the Lao Gan Ma packaging has never modernized: it’s been the same old-fashioned logo for decades.

It is a marketing strategy that follows Tao’s no-nonsense line of thinking: if your product is good enough, people will buy it again. “We’re selling the flavor, not the packaging,” Tao herself once said.

3: The Old Godmother: “Labor Builds the Chinese Dream”

In the eyes of many, Tao Huabi is an embodiment of the ‘Chinese dream.’ A few years ago, Chinese state broadcaster CCTV produced a TV series titled “Labor Builds the Chinese Dream” (劳动铸就中国梦), and one of its episodes featured Tao Huabi, who is now 74 years old.

The main narrative of the documentary is that all people built on a country’s wealth together with each other as a collective goal – not an individual one. The idea of the ‘China Dream’ has been especially ubiquitous in Chinese official media since Xi Jinping became president in 2013. The concept refers to “the great rejuvenation of the Chinese nation.” In his first address to the nation in March of 2013, Xi emphasized that in order to realise the “Chinese road”: “(..) we must spread the Chinese spirit, which combines the spirit of the nation with patriotism as the core and the spirit of the time with reform and innovation as the core.”

Tao’s story fits this idea of the Chinese shared ‘road to prosperity’ dream. She started out poor but created her own business in spite of all obstacles. Along the way, she was always prepared to help out others while she herself rarely relied on her network or other people’s money to reach her goals.

Throughout her business journey, Tao has stayed true to her province, earning her the “Miracle of Guizhou” nickname. Despite the many offers she had throughout her career to set up her business elsewhere, she always refused to leave her home base – much to the delight of local government officials who have continuously shown their support for Tao. The businesswoman is a blessing for the province; not just because her brand has become known as a unique ‘product of Guizhou’, but mainly because she offers employment to nearly 5000 staff members, and directly and indirectly generates income for ten-thousands of local farmers.

Tao is also a Party member, and she is politically active as, among others, a representative of the Standing Committee of the Guizhou Provincial People’s Congress. She attended the National People’s Congress in Beijing multiple times.

Tao Huabi at the Two Sessions, photo via Sohu.com.

While Lao Gan Ma is one of China’s national brands, Tao Huabi is often also seen as a patriotic entrepreneur. Lao Gan Ma’s condiments are much more expensive outside in foreign countries than in China. While a two-pack of Lao Gan Ma is sold for only 9.9 yuan ($1.5) on Chinese e-commerce platform Taobao, the same pack is sold in the US for 13 up to 18 dollars on the American Amazon: eight to twelve times more expensive than the Chinese price. When asked about the enormous Lao Gan Ma price difference between China and other countries, Tao said: “I’m Chinese. I don’t make money off of Chinese people. I want to sell Lao Gan Ma to foreign countries and make money off of foreigners.”

Lao Gan Ma’s popularity outside of China has risen over the past decade. On Facebook, there is even a public group called “The Lao Gan Ma (老干妈) Appreciation Society,” where the group members (over 4000!) share their love for the brand.

Examples of Tao Huabi featured in fashion and accessories. Tao Huabi as a fashion icon?!

Meanwhile, on Chinese social media platform Weibo, Lao Gan Ma and Tao Huabi’s story often pop up in people’s posts: “Old Godmother is an example that you can still make it in life without any education.”

Perhaps there is no better person to embody the Chinese dream than Tao Huabi, who has experienced life in China from so many different angles. A poor farmer’s daughter, a young struggling widow, a migrant factory worker, a loving mother, a roadside peddler, a business manager, a loyal Party member, and even an unexpected fashion icon – Tao Huabi has seen and been it all. There is one thing she will always be: China’s chili sauce queen.

By Manya Koetse

Follow @whatsonweibo

1 Zhang Nali 张丽娜. 2019 (2016). Tao Huabi, Founder of Lao Gan Ma: If I Wouldn’t Have Been Strong, I Would’ve Starved [老干妈创始人陶华碧 我不坚强就没得饭吃] (in Chinese). Beijing: Chinese Publishing House. ISBN 978-7-5075-4451-0.

Featured image by Ama for Yi Magazin.

This text was written for Goethe-Institut China under a CC-BY-NC-ND-4.0-DE license (Creative Commons) as part of a monthly column in collaboration with What’s On Weibo.

Spotted a mistake or want to add something? Please let us know in comments below or email us. First-time commenters, please be patient – we will have to manually approve your comment before it appears.

Manya Koetse is the founder and editor-in-chief of whatsonweibo.com. She is a writer, public speaker, and researcher (Sinologist, MPhil) on social trends, digital developments, and new media in an ever-changing China, with a focus on Chinese society, pop culture, and gender issues. She shares her love for hotpot on hotpotambassador.com. Contact at manya@whatsonweibo.com, or follow on Twitter.

China Brands, Marketing & Consumers

A Brew of Controversy: Lu Xun and LELECHA’s ‘Smoky’ Oolong Tea

Chinese tea brand LELECHA faced backlash for using the iconic literary figure Lu Xun to promote their “Smoky Oolong” milk tea, sparking controversy over the exploitation of his legacy.

Published

4 days agoon

May 3, 2024

It seemed like such a good idea. For this year’s World Book Day, Chinese tea brand LELECHA (乐乐茶) put a spotlight on Lu Xun (鲁迅, 1881-1936), one of the most celebrated Chinese authors the 20th century and turned him into the the ‘brand ambassador’ of their special new “Smoky Oolong” (烟腔乌龙) milk tea.

LELECHA is a Chinese chain specializing in new-style tea beverages, including bubble tea and fruit tea. It debuted in Shanghai in 2016, and since then, it has expanded rapidly, opening dozens of new stores not only in Shanghai but also in other major cities across China.

Starting on April 23, not only did the LELECHA ‘Smoky Oolong” paper cups feature Lu Xun’s portrait, but also other promotional materials by LELECHA, such as menus and paper bags, accompanied by the slogan: “Old Smoky Oolong, New Youth” (“老烟腔,新青年”). The marketing campaign was a joint collaboration between LELECHA and publishing house Yilin Press.

Lu Xun featured on LELECHA products, image via Netease.

The slogan “Old Smoky Oolong, New Youth” is a play on the Chinese magazine ‘New Youth’ or ‘La Jeunesse’ (新青年), the influential literary magazine in which Lu’s famous short story, “Diary of a Madman,” was published in 1918.

The design of the tea featuring Lu Xun’s image, its colors, and painting style also pay homage to the era in which Lu Xun rose to prominence.

Lu Xun (pen name of Zhou Shuren) was a leading figure within China’s May Fourth Movement. The May Fourth Movement (1915-24) is also referred to as the Chinese Enlightenment or the Chinese Renaissance. It was the cultural revolution brought about by the political demonstrations on the fourth of May 1919 when citizens and students in Beijing paraded the streets to protest decisions made at the post-World War I Versailles Conference and called for the destruction of traditional culture[1].

In this historical context, Lu Xun emerged as a significant cultural figure, renowned for his critical and enlightened perspectives on Chinese society.

To this day, Lu Xun remains a highly respected figure. In the post-Mao era, some critics felt that Lu Xun was actually revered a bit too much, and called for efforts to ‘demystify’ him. In 1979, for example, writer Mao Dun called for a halt to the movement to turn Lu Xun into “a god-like figure”[2].

Perhaps LELECHA’s marketing team figured they could not go wrong by creating a milk tea product around China’s beloved Lu Xun. But for various reasons, the marketing campaign backfired, landing LELECHA in hot water. The topic went trending on Chinese social media, where many criticized the tea company.

Commodification of ‘Marxist’ Lu Xun

The first issue with LELECHA’s Lu Xun campaign is a legal one. It seems the tea chain used Lu Xun’s portrait without permission. Zhou Lingfei, Lu Xun’s great-grandson and president of the Lu Xun Cultural Foundation, quickly demanded an end to the unauthorized use of Lu Xun’s image on tea cups and other merchandise. He even hired a law firm to take legal action against the campaign.

Others noted that the image of Lu Xun that was used by LELECHA resembled a famous painting of Lu Xun by Yang Zhiguang (杨之光), potentially also infringing on Yang’s copyright.

But there are more reasons why people online are upset about the Lu Xun x LELECHA marketing campaign. One is how the use of the word “smoky” is seen as disrespectful towards Lu Xun. Lu Xun was known for his heavy smoking, which ultimately contributed to his early death.

It’s also ironic that Lu Xun, widely seen as a Marxist, is being used as a ‘brand ambassador’ for a commercial tea brand. This exploits Lu Xun’s image for profit, turning his legacy into a commodity with the ‘smoky oolong’ tea and related merchandise.

“Such blatant commercialization of Lu Xun, is there no bottom limit anymore?”, one Weibo user wrote. Another person commented: “If Lu Xun were still alive and knew he had become a tool for capitalists to make money, he’d probably scold you in an article. ”

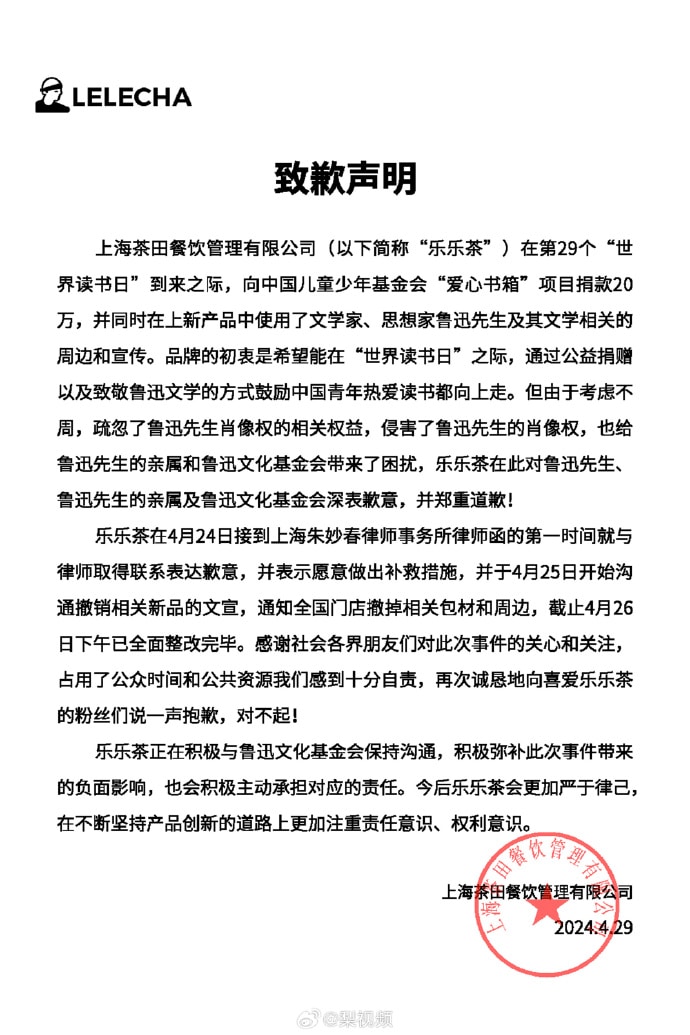

On April 29, LELECHA finally issued an apology to Lu Xun’s relatives and the Lu Xun Cultural Foundation for neglecting the legal aspects of their marketing campaign. They claimed it was meant to promote reading among China’s youth. All Lu Xun materials have now been removed from LELECHA’s stores.

Statement by LELECHA.

On Chinese social media, where the hot tea became a hot potato, opinions on the issue are divided. While many netizens think it is unacceptable to infringe on Lu Xun’s portrait rights like that, there are others who appreciate the merchandise.

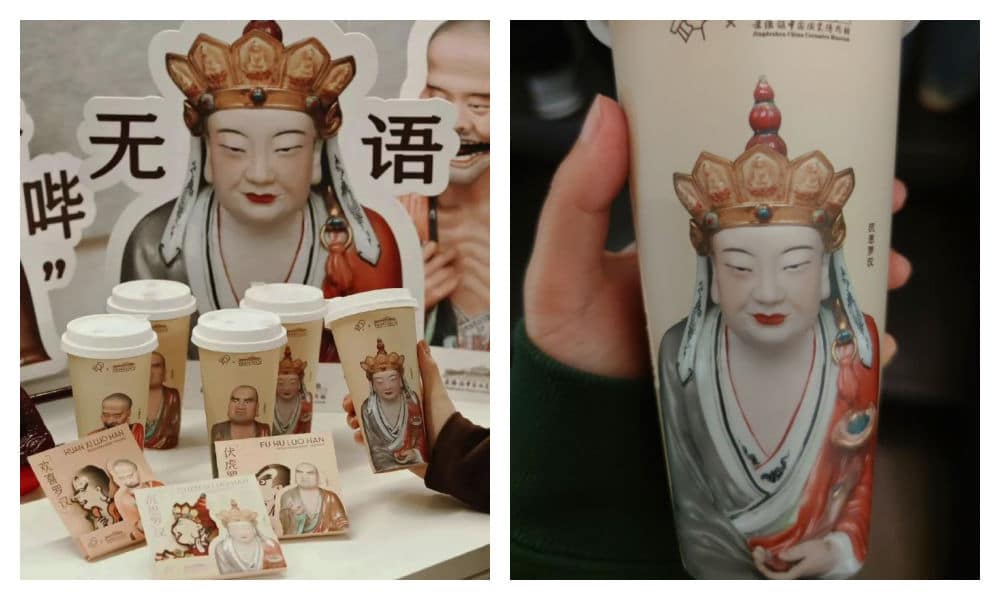

The LELECHA controversy is similar to another issue that went trending in late 2023, when the well-known Chinese tea chain HeyTea (喜茶) collaborated with the Jingdezhen Ceramics Museum to release a special ‘Buddha’s Happiness’ (佛喜) latte tea series adorned with Buddha images on the cups, along with other merchandise such as stickers and magnets. The series featured three customized “Buddha’s Happiness” cups modeled on the “Speechless Bodhisattva” (无语菩萨), which soon became popular among netizens.

The HeyTea Buddha latte series, including merchandise, was pulled from shelves just three days after its launch.

However, the ‘Buddha’s Happiness’ success came to an abrupt halt when the Ethnic and Religious Affairs Bureau of Shenzhen intervened, citing regulations that prohibit commercial promotion of religion. HeyTea wasted no time challenging the objections made by the Bureau and promptly removed the tea series and all related merchandise from its stores, just three days after its initial launch.

Following the Happy Buddha and Lu Xun milk tea controversies, Chinese tea brands are bound to be more careful in the future when it comes to their collaborative marketing campaigns and whether or not they’re crossing any boundaries.

Some people couldn’t care less if they don’t launch another campaign at all. One Weibo user wrote: “Every day there’s a new collaboration here, another one there, but I’d just prefer a simple cup of tea.”

By Manya Koetse

[1]Schoppa, Keith. 2000. The Columbia Guide to Modern Chinese History. New York: Columbia UP, 159.

[2]Zhong, Xueping. 2010. “Who Is Afraid Of Lu Xun? The Politics Of ‘Debates About Lu Xun’ (鲁迅论争lu Xun Lun Zheng) And The Question Of His Legacy In Post-Revolution China.” In Culture and Social Transformations in Reform Era China, 257–284, 262.

Independently reporting China trends for over a decade. Like what we do? Support us and get the story behind the hashtag by subscribing:

Spotted a mistake or want to add something? Please let us know in comments below or email us. First-time commenters, please be patient – we will have to manually approve your comment before it appears.

©2024 Whatsonweibo. All rights reserved. Do not reproduce our content without permission – you can contact us at info@whatsonweibo.com.

China Brands, Marketing & Consumers

Zara Dress Goes Viral in China for Resemblance to Haidilao Apron

Who’s gonna buy this Zara dress in China? “I’m afraid that someone will say I stole the apron from Haidilao.”

Published

3 weeks agoon

April 19, 2024

A short dress sold by Zara has gone viral in China for looking like the aprons used by the popular Chinese hotpot chain Haidilao.

“I really thought it was a Zara x Haidialo collab,” some customers commented. Others also agree that the first thing they thought about when seeing the Zara dress was the Haidilao apron.

The “original” vs the Zara dress.

The dress has become a popular topic on Xiaohongshu and other social media, where some images show the dress with the Haidilao logo photoshopped on it to emphasize the similarity.

One post on Xiaohongshu discussing the dress, with the caption “Curious about the inspiration behind Zara’s design,” garnered over 28,000 replies.

Haidilao, with its numerous restaurants across China, is renowned for its hospitality and exceptional customer service. Anyone who has ever dined at their restaurants is familiar with the Haidilao apron provided to diners for protecting their clothes from food or oil stains while enjoying hotpot.

These aprons are meant for use during the meal and should be returned to the staff afterward, rather than taken home.

The Haidilao apron.

However, many people who have dined at Haidilao may have encountered the following scenario: after indulging in drinks and hotpot, they realize they are still wearing a Haidilao apron upon leaving the restaurant. Consequently, many hotpot enthusiasts may have an ‘accidental’ Haidilao apron tucked away at home somewhere.

This only adds to the humor of the latest Zara dress looking like the apron. The similarity between the Zara dress and the Haidilao apron is actually so striking, that some people are afraid to be accused of being a thief if they would wear it.

One Weibo commenter wrote: “The most confusing item of this season from Zara has come out. It’s like a Zara x Haidilao collaboration apron… This… I can’t wear it: I’m afraid that someone will say I stole the apron from Haidilao.”

Funnily enough, the Haidilao apron similarity seems to have set off a trend of girls trying on the Zara dress and posting photos of themselves wearing it.

It’s doubtful that they’re actually purchasing the dress. Although some commenters say the dress is not bad, most people associate it too closely with the Haidilao brand: it just makes them hungry for hotpot.

By Manya Koetse

Independently reporting China trends for over a decade. Like what we do? Support us and get the story behind the hashtag by subscribing:

Spotted a mistake or want to add something? Please let us know in comments below or email us. First-time commenters, please be patient – we will have to manually approve your comment before it appears.

©2024 Whatsonweibo. All rights reserved. Do not reproduce our content without permission – you can contact us at info@whatsonweibo.com.

Subscribe

A Brew of Controversy: Lu Xun and LELECHA’s ‘Smoky’ Oolong Tea

Weibo Watch: The Battle for the Bottom Bed

Zara Dress Goes Viral in China for Resemblance to Haidilao Apron

“Old Bull Eating Young Grass”: 86-Year-Old Chinese Painter Fan Zeng Marries 36-Year-Old Xu Meng

Chengdu Disney: The Quirkiest Hotspot in China

The ‘Two Sessions’ Suggestions: Six Proposals Raising Online Discussions

Top 9 Chinese Movies to Watch This Spring Festival Holiday

“Old Bull Eating Young Grass”: 86-Year-Old Chinese Painter Fan Zeng Marries 36-Year-Old Xu Meng

Party Slogan, Weibo Hashtag: “The Next China Will Still Be China”

From Pitch to Politics: About the Messy Messi Affair in Hong Kong (Updated)

Chengdu Disney: The Quirkiest Hotspot in China

Looking Back on the 2024 CMG Spring Festival Gala: Highs, Lows, and Noteworthy Moments

More than Malatang: Tianshui’s Recipe for Success

Two Years After MU5735 Crash: New Report Finds “Nothing Abnormal” Surrounding Deadly Nose Dive

The Chinese Viral TikTok Song Explained (No, It’s Not About Samsung)

Get in touch

Would you like to become a contributor, or do you have any tips or suggestions? Get in touch here!

Popular Reads

-

China Insight2 months ago

China Insight2 months agoThe ‘Two Sessions’ Suggestions: Six Proposals Raising Online Discussions

-

China Arts & Entertainment3 months ago

China Arts & Entertainment3 months agoTop 9 Chinese Movies to Watch This Spring Festival Holiday

-

China Arts & Entertainment3 weeks ago

China Arts & Entertainment3 weeks ago“Old Bull Eating Young Grass”: 86-Year-Old Chinese Painter Fan Zeng Marries 36-Year-Old Xu Meng

-

China Media2 months ago

China Media2 months agoParty Slogan, Weibo Hashtag: “The Next China Will Still Be China”

Godfree Roberts

August 23, 2021 at 8:44 am

“During the Great Chinese Famine (1959-1961)”??

There was no Great Chinese Famine between 1959-1961. There were three difficult years, but nobody starved to death.

There was a Great Chinese Famine in 1942, during which millions starved to death, but that’s another matter.

There is a claimed, Great Famine in 1959-61, but the claims lack evidence, motive, or explanation and the book by the principal claimant, Frank Dikotter, is untrustworthy–even on its face. The cover image of a starving Chinese child was taken in 1942 (because, the author explained, “I couldn’t find any pictures of starvation from 1959-60).

There WAS an El Nino event from 1959-60 and there WAS an American embargo on exporting grain to China–designed to starve the country into submission, but even the CIA admitted that it had not failed:

April 4, 1961: The Chinese Communist regime is now facing the most serious economic difficulties it has confronted since it concentrated its power over mainland China. As a result of economic mismanagement, and especially of two years of unfavorable weather, food production in 1960 was hardly larger than in 1957, at which time there were about 50 million fewer Chinese to feed. Widespread famine does not appear to be at hand. Still, in some provinces, many people are now on a bare subsistence diet, and the bitterest suffering lies immediately ahead, in the period before the July harvests. The dislocations caused by the ‘Leap Forward’ and the removal of Soviet technicians have disrupted China’s industrialization program. These difficulties have sharply reduced the rate of economic growth during 1960 and have created a severe balance of payments problem. Public morale, especially in rural areas, is almost certainly at its lowest point since the Communists assumed power, and there have been some instances of open dissidence.

May 2, 1962: The future course of events in Communist China will be shaped largely by three highly unpredictable variables: the wisdom and realism of the leadership, the level of agricultural output, and the nature and extent of foreign economic relations. During the past few years, all three variables have worked against China. In 1958, the leadership adopted a series of ill-conceived and extremist economic and social programs; in 1959, there occurred the first of three years of bad crop weather; and in 1960, Soviet economic and technical cooperation was largely suspended. The combination of these three factors has brought economic chaos to the country. Malnutrition is widespread, foreign trade is down, and industrial production and development have dropped sharply. No quick recovery from the regime’s economic troubles is in sight.

Ridiculing the Great Leap Forward as ‘The Great Leap Backward,’ Edgar Snow confirmed the CIA’s findings:

Were the 1960 calamities as severe as reported in Peking, ‘the worst series of disasters since the nineteenth century,’ as Chou En-lai told me? The weather was not the only cause of the disappointing harvest, but it was undoubtedly a major cause. With good weather, the crops would have been ample; without it, other adverse factors I have cited–some discontent in the communes, bureaucracy, transportation bottlenecks–weighed heavily. Merely from personal observations in 1960, I know that there was no rain in large areas of northern China for 200-300 days. I have mentioned unprecedented floods in central Manchuria where I was marooned in Shenyang for a week …while eleven typhoons struck northeast China–the largest number in fifty years, and I saw the Yellow River reduced to a small stream. Throughout 1959-1962, many Western press editorials continued referring to ‘mass starvation’ in China and continued citing no supporting facts. As far as I know, no report by any non-Communist visitor to China provides an authentic instance of starvation during this period. Here I am not speaking of food shortages, or lack of surfeit, to which I have made frequent reference, but of people dying of hunger, which is what ‘famine’ connotes to most of us, and what I saw in the past.

Felix Greene, too, traveled throughout China in 1960:

With the establishment of the new Government in Peking in 1949, two things happened. First, starvation–death by hunger–ceased in China. There have been food shortages–and severe ones, but no starvation–a fact fully documented by Western observers. The truth is that the sufferings of the ordinary Chinese peasant from war, disorder, and famine have been immeasurably less in the last decade than in any other decade in the century.

Sky

March 13, 2024 at 6:53 pm

It is Zhang Li Na not Zhang Nali.

Manya

March 25, 2024 at 1:17 pm

Adjusted, thanks!